Key takeaways

Crew incompetence

This is a well-established potential cause of unseaworthiness.

Defective passage planning

This has to be causative of the casualty in order to render the vessel unseaworthy.

Due diligence

Owners need reliable and adequate evidence they exercised due diligence to render the vessel seaworthy.

Unity Ship Group S.A. -v- Euroins Insurance JSC (Happy Aras) [2025] EWHC 7 (Admty)

On 12 January 2026, in its first judgment of the year, the Admiralty Court has dealt with a general average claim following a casualty and found that the vessel was unseaworthy at the relevant time and that owners had failed to establish that they had exercised due diligence.

The background facts

The HAPPY ARAS is a Belize registered, 94m, 2,659 gross tonne bulk carrier. On 20 March 2023, while laden with soya beans on a voyage from Reni, Ukraine, to Mersin, Turkey, she grounded at 20:58 local time on the north shore of the Datça peninsula in southern Turkey. The vessel sustained substantial damage, and a complex salvage, lightering and transhipment followed, concluding on 13 June 2023.

Following the casualty, the vessel owners declared General Average (GA) and sought the cargo contribution, assessed at approximately US$1.27 million. Cargo interests denied GA liability on the basis that the owners had breached their due diligence obligations to render the vessel seaworthy under Article III Rule 1 of the Hague Rules.

The grounding

It is notable that there was limited evidence available on the navigation in this case. The vessel was not required to be fitted with a VDR and was navigating using a radar and a paper chart, with GPS fixes to be plotted. However, no fixes were plotted or logged in the hour before the grounding. No evidence was given by the crew, save for very brief statements being made available that had been given before the Turkish Commercial Court shortly after the grounding. However, AIS data was publicly available and used to recreate the vessel’s track.

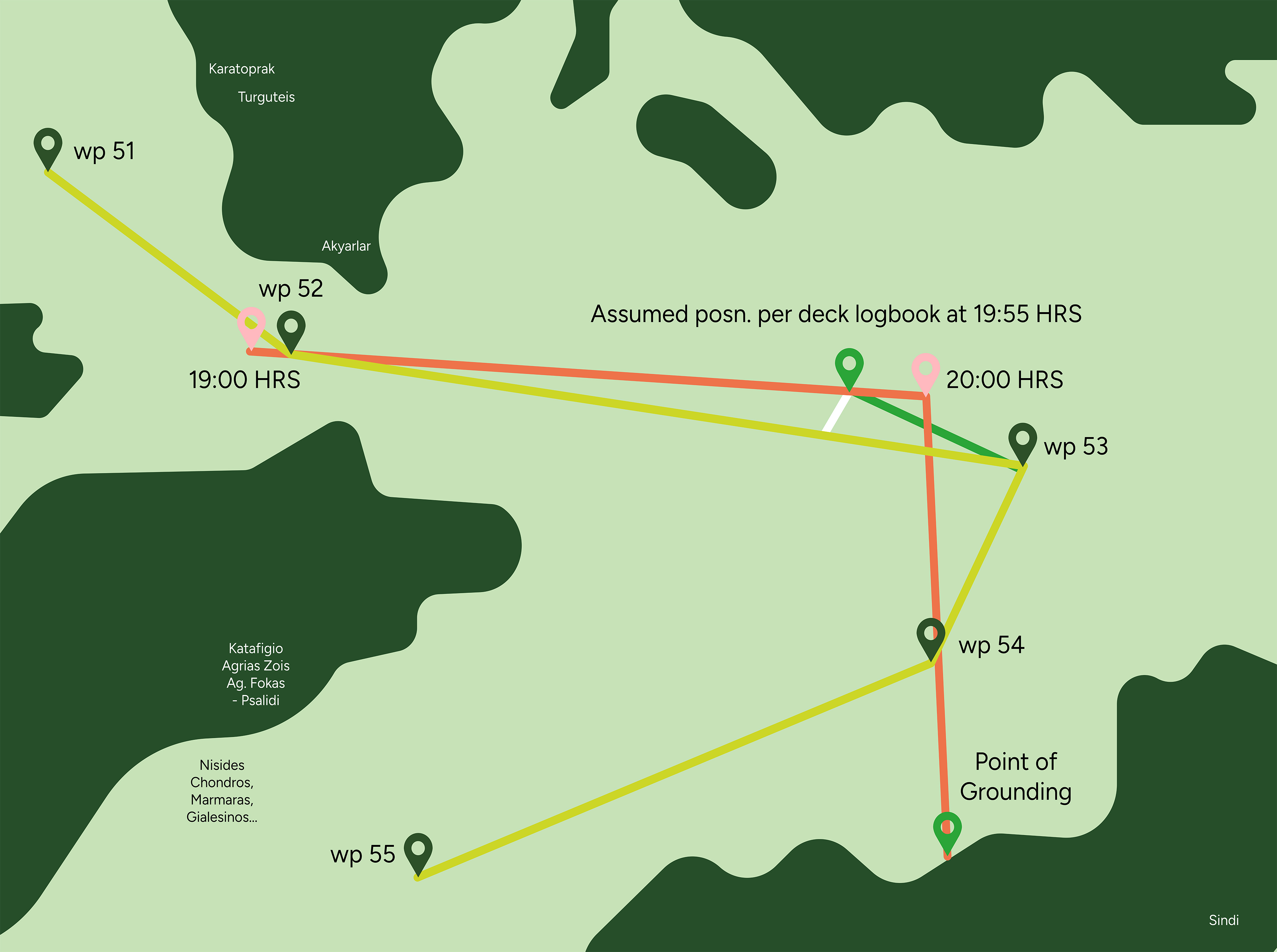

Figure 1 below is the image shows the vessel’s Passage Plan route (lime green line) and the approximate track of the vessel taken (orange line).

At 20:00, whilst approaching a planned waypoint off the Datça peninsula, the Master, who had taken over as Officer of the Watch, “cut the corner” by altering early to a southerly heading towards waypoint 54 and failed to plot or log any fixes, despite the passage plan calling for them at intervals every 10 minutes.

Shortly after sunset, and before waypoint 54, the Master sent the lookout below to make tea. The Master was alone on the bridge and missed the scheduled waypoint 54 alteration to 231°. The ship continued south at about 9 knots towards the land with no effective corrective helm or engine action and no meaningful use of radar or bridge watch alarms. The vessel entered shallow water shortly before 20:58 and grounded within seconds. Regarding the sequence of events leading up to the grounding, there was little, if any, dispute between the parties’ respective marine experts.

The legal issue

The judgment provides a useful recap of the law of contract of carriage and unseaworthiness.

In brief, the contract of carriage incorporated the Hague Rules, placing an obligation on the owner to render the vessel seaworthy before and at the beginning of the voyage. The burden of proving unseaworthiness is on cargo interests.

Nevertheless, even if cargo interests are successful in showing that the vessel was causatively unseaworthy, the owners will only be in breach of the Hague Rules if they failed to meet their non-delegable duty of due diligence to make the vessel seaworthy at the commencement of the voyage. However, the burden of proving that due diligence is on the owners. If the owners fail to evidence that they exercised due diligence, then their GA claim will fail. Cargo interests argued that the vessel was unseaworthy in two respects:

the vessel was not properly manned with a competent crew (in particular, the Master); and

the vessel’s passage plan was defective and fell short of recognised standards.

Cargo interests argued that both the above alleged instances of unseaworthiness caused the grounding (although see cargo’s position regarding passage planning below) and owners had not exercised due diligence. As such, they argued that owners cannot recover in GA.

Unseaworthiness claim 1: crew incompetence

Cargo interests pleaded that the vessel was unseaworthy because it was not manned by a competent crew. Crew incompetence is a well-established potential cause of unseaworthiness.

The focus was on the Master’s conduct in the hour leading up to the grounding. Cargo interests noted the following instances of incompetence:

an unplanned early alteration of course from the track in the passage plan;

failure to take and record position fixes at the required intervals;

sending the lookout below during hours of darkness and remaining alone on the bridge; and

missing a planned alteration at a waypoint and continuing towards shoal water.

The owners emphasised that there was a distinction between negligence and incompetence, stressing there is a “wide gulf” between the two. In this instance, the owners argued that the Master was negligent rather than incompetent because the Master’s errors in this case were isolated, casual errors.

Additionally, owners argued that they complied with their due diligence obligations, pointing to the following to establish that there was no reason to doubt the Master’s capabilities at the start of the voyage:

the Master’s valid certificates of competency;

his three year service with the owners;

prior employment on similar tonnage vessels;

a “positive reference” from a reputable previous employer; and

internal “performance evaluation” results.

However, this evidence was only supported by a hearsay statement made by the beneficial owner of the vessel, rather than any documentation.

Unseaworthiness claim 2: defective passage plan

Cargo interests also pleaded that the vessel’s passage plan was defective. They argued that the passage plan was said to be basic and incomplete in parts, lacking features often used in modern practice, such as cross track limits (which could have been entered on the radar) and/or clearly marked no go areas.

Defective passage planning is a well-established potential cause of unseaworthiness, especially in light of the relatively recent CMA CGM Libra decisions. Of note, cargo interests’ counsel also argued on behalf of cargo interests that if the passage plan was defective, it was not necessary for her to prove that the defects were causative.

The owners’ expert witness accepted the plan was “basic” but explained that features criticised by cargo interests (such as explicit no go areas and cross track limits) are desirable rather than mandated entries in the written plan, and that around Datça the steeply shelving seabed makes the coastline itself the effective no go boundary.

The expert further noted that cross track and proximity alerts can be configured on bridge systems even if they are not recorded on the paper plan, and there was no direct evidence they were absent.

Crucially, both parties’ expert witnesses agreed that despite its issues, had the passage plan been followed the grounding would not have occurred.

The Admiralty Court decision

Crew competency

Despite having valid certificates of competence, the Court found the Master to be incompetent. The court cited the case of The Farrandoc [1967] 2 Lloyd’s Rep. 276 which established that it is not necessarily enough to rely on a mariner’s certificates to establish their competency.

Perhaps the clearest reason for this is the Admiralty Registrar’s finding that:

“The grounding was not the product of an isolated error. The errors were numerous and egregious and can be characterized as a complete dereliction of duty.”

He also found that:

“A prudent owner would have required the relevant defect (in this case the competence of the Master), had he known of it, to be made good before sending his ship to sea.”

The Admiralty Registrar found that these failures rendered the vessel unseaworthy at the material time.

The burden then shifted to the owners to prove that they had exercised due diligence in the appointment and supervision of the Master. However, other than the beneficial owner’s hearsay statement, there was little evidence of the due diligence allegedly undertaken.

For example, copies of the “positive reference” and “performance evaluations” were never disclosed. Ultimately, the owners did not discharge the due diligence burden, and so cargo interests’ defence against having to pay any GA contributions succeeded and the owners’ GA claim failed.

Passage planning

Notwithstanding the claim failed on the basis of crew incompetence, the Court also dealt with whether the passage plan was defective and whether it rendered the vessel unseaworthy, and/or was causative of the grounding.

The Admiralty Registrar noted that both experts agreed that, had the Passage Plan been followed, the grounding would not have occurred and found that the defects were not causative. He agreed that the passage plan was basic, and contained “defects”, but found that this placed a greater burden on the Master to competently discharge his duty as Master and Officer of the Watch.

Although these defects were considered “part of the picture”, the Admiralty Registrar found that the passage plan on its own did not render the vessel unseaworthy. This might be surprising, but the Registrar presumably considered the “defects” were not serious enough. It was irrelevant anyway given the defective passage plan was not causative.

Regarding cargo interests’ argument that any unseaworthiness does not need to be causative, Admiralty Registrar Davison disagreed and made short work of this by citing the opening sentence set out in the headnote of the Lloyd’s Law Report of The CMA CGM Libra judgment:

“The Article IV rule 2(a) exception of act, neglect or default in the navigation or management of the ship could not be relied upon in relation to a causative breach of the carrier’s obligation to exercise due diligence to make the ship seaworthy”.

Accordingly, cargo interests’ defence did not succeed in this regard.

Comment

Casualty claims handlers and lawyers reading this case will not be surprised by the defences raised by cargo interests in the HAPPY ARAS. Following the CMA CGM Libra decision, it is common that cargo interests try to establish that a casualty was caused by defective passage planning. However, this allegation is often made without sufficient merit, with cargo interests failing to identify any causative defects (as was the case here).

Alongside passage planning, cargo interests also argue (almost as a matter of course), that the shortcomings in crew competence renders the vessel unseaworthy and is the effective cause of a casualty, as was successfully argued here.

Crew competence is clearly, and quite rightly, a critical element of seaworthiness, but a finding of incompetence rather than mere negligence, remains a high bar to reach, for all the reasons set out in this judgment. The HAPPY ARAS is a good example of the extent to which there must be a dereliction of duty in order to render a vessel unseaworthy.

The HAPPY ARAS is also a good example of the importance of an owner being able to prove due diligence with reliable evidence. The evidentiary burden lays with the owner, and certificates of competencies alone will not suffice. The English courts have made it clear owners need to go further to prove that they discharged their due diligence obligations.